Boyd on Bond Q&A (2)

5th November 2013

Read a full transcript of Boyd's public Q&A session at the Southbank, celebrating the UK launch of 'Solo'

By Ben Williams

By Ben Williams

Olivia Cole

One of the newspapers already said, "Boyd is Bond" in their review, which is a great complement, but also very frustrating. You are a real chameleon as a novelist...but how do you go from being a civilised novelist...to this character who is, in some ways, a sociopath? How do you approach it?

William Boyd Olivia Cole |

|

William Boyd

It is difficult, because in the first Bond novels, Fleming had Bond born much earlier, around about his own birth date, pre World War I. So, Bond is a creature of that Edwardian English background. As the novels went on he decreased Bond's age until he eventually decided that he was born in 1924, so he's that World War II generation. But Bond is no fool...I would imagine that an intelligent man looking about him would (notice the changes). Bond lived in Chelsea, just off the Kings Road - the most fashionable street in the world at the time- and Bond wandering up the road to buy a pint of milk couldn't have helped but notice that the world had changed enormously. And being an intelligent, sentient being, his attitudes would have changed. He's still the old Bond, but you couldn't continue living in a rut in the late 60s, especially living in Chelsea, so I sort of knocked the rough edges off him a bit, but I think that's entirely plausible.

Olivia Cole

You've said that you prefer to think of (the heroines) as Bond women and not Bond girls. When you went back to the books, what did you make of those relationships and how did you set about writing (the heroine)? Who were your favourites of the old books?

William Boyd

I quite like Tatiana from "From Russia, With Love", and I'm quite intrigued by Honeychile Rider in "Dr. No", as well. Interestingly, a lot of the women in the novels - and I refer to them as women not Bond Girls, because I want to keep this gap between the film Bond and the literary Bond - they're quite damaged and they're troubled, like him. His wife, whom he married to for barely a day before she was shot, was called Tracy di Vicenzo, and Bond saved her from committing suicide. Well, would you want to marry a potential suicide? Clearly he did. I have an actor friend who has had all sorts of mental problems, who said: "I go into a room of two-hundred people and will find the most damaged person in that room. I don't know how it happens, but we're drawn to each other." And so I feel that Bond, with all his complexities with this dark side to him - I mean, he weeps openly in the novels, the tears flow. He's a man of feeling. He vomits when he sees something horrible or gory - seems attracted to these women who are troubled. So, it's far more complex. Even though, I must admit, that some of the early descriptions (of women by Fleming) are sado-sexist, and you can't possibly condone them at all, even within their context. But I think that Fleming was of that generation and of that class where these attitudes were unreflecting. I think that he was an unreflecting racist, probably an unreflecting anti-Semite, right wing, sexist, and homophobe...but accuse him of being a racist and he'd have been outraged. He was very much of the time and class, I think. He was unreflecting and I think that's why it comes across now so starkly.

|

Olivia Cole

Do you think he understood women in any way? His character is this famous womanizer. Do you think that's something that reflected his own life and his own relationships?

William Boyd

No, I don't think so. I think he had very complex relationships with women, as far as one can determine. I was going through letters, biographies, and memoirs of people who knew him and his marriage was very complex. Ann Fleming, he was her third husband, she was his first wife, and they both very quickly began affairs. They had one son, who committed suicide at age 23, so, it wasn't the happiest of households...Fleming wasn't Bond, in any sense, but he gave Bond all his traits, and all his tastes, and his needs, and desires, and wants, and complexes, and troubles. Bond is very aware of women's clothing, for example, in a way that's very atypical, but Fleming was, too. Analyzing the dress, the material, the cut, and all that sort of thing, that's unusual for a man of that class and time. But Bond does that, as you can tell from that little extract. He notices that it's a jersey cat suit - not many men in 1969 did that, unless they're in the rag trade, I suspect. So, it's a Fleming trait that Bond has. All of Bond's bad habits are Fleming's: 70 cigarettes-a-day, a bottle-and-a-half of vodka, haphazard and casual use of Benzedrine - again, something that men of his class took without thinking.

Olivia Cole

You've also created a fantastic villain, Kobius Breed, who is a mercenary complete with a missing cheekbone and a watery eye. How did you go about creating a memorable villain? Bond often has an admiration for the creativity of his foes, which is quite important.

William Boyd

When I met with the Fleming family and we talked about writing the novel, I told them that I wanted to write a realistic novel about a real person, because I'm a realistic novelist and I didn't want to write a fantastical, grotesque, or totally implausible spy. I wanted to write a real, gritty spy novel, of a man, 45 year-old spy, who'd been sent on a mission. And so, when I thought of a villain, because that is one of the givens that you have in a Bond novel, that the villain has to be memorable, I thought I'd make him realistic. Bond goes to Africa to try to stop the civil war - no pressure! - and the man he meets there, Kobius Breed, is fresh from The Bush War in Rhodesia and has been very badly wounded in the face and in the head, in every sense of the word. He has been shot in the face twice by a ZANLA terrorist and, as a result, half of his face has collapsed and one eye constantly produces tears, which he has to brush away. So, he's the man with two faces; the other half of his face is fine. He's a really nasty, psychopathic mercenary, soldier of the sort that one could have encountered then, or indeed now. He's not a Blofeld or somebody running some global crime organization. He's just a really nasty piece of work, fighting a nasty little African war.

Olivia Cole

Ian Fleming had the Cold War going on as he was writing, but were there any other events that were happening in that period that you thought you could throw Bond's way?

William Boyd

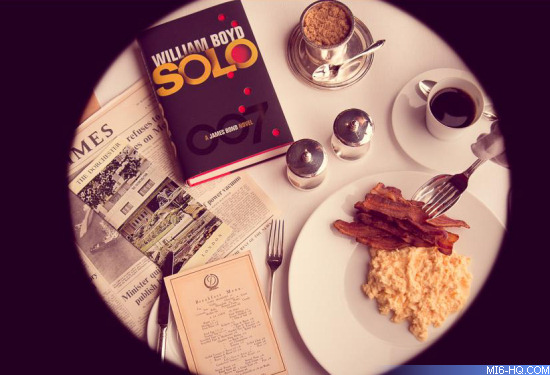

I could have. The Vietnam War, for instance. When Bond's having his breakfast, shortly after the episode (described in the extract) he's offered a copy of The Times with the headline "Viet Cong Offensive Halted With Many Casualties" and he says: "not today, thank you". So, it is a very interesting period of history. Bond goes to Washington DC in the second half of the novel and Washington in '69 was possibly the most dangerous city in the USA. Martin Luther King had been assassinated the year before and great blocks of the city had been torched, there had been riots, and apart from the central governmental district, it was a very, very dangerous city to go to. So, that reflects the social reality of the ‘69. I've been to Washington lots of times and it's nothing like it was then, but I knew two friends who lived in the city in the late 60s and early 70s and they told me what it was like. The moon landing took place in July '69, which I remember very vividly, and there's an allusion to it. I sort of positioned things happen. The girl he has an affair with in Africa, who is half Zanzari and half English, has an Afro hairstyle. So, there are little details of the time. But I wanted to take him to Africa and I wanted to take him to the USA.

|

Olivia Cole

You're adamant that Bond was well read. The book that he reads on the plane is Graham Greene's "The Heart of the Matter", which is quite a sophisticated choice. In Fleming's books he reads JFK's booklets, he reads about the CIA. I wonder, what makes your Bond acquire his library?

William Boyd

Well, it's interesting because, as I read through the novels, I kept coming across literary references. Sometimes he reads Eric Ambler, a thriller writer of that era, he reads a lot of books on golf and bridge and cards. But he also refers to writers in a throwaway manner, one, for example, who nobody will have heard of, called Lafcadio Hearn, who was an Englishman but was an expert on Japanese literature and Japanese life. And then there are a few throwaway quotes, which Fleming doesn't identify in the novels, which I tracked down. One of them is from Milton's "Paradise Lost" - surprise, surprise - and there is another line of poetry, which is unattributed, that is from a little known American poet called Ralph Waldo Emerson. I haven't read any Ralph Waldo Emerson! So, this is quite recherché reading. And given the "book-lined room" that Fleming describes when he's describing Bond's catalogue, this is eclectic reading. Bond is obviously some sort of autodidact. He left school at 17, but he's well read. You can't just throw in the poetry of Milton without knowing what you're talking about. I thought that as he is going to West Africa, the great novel on West Africa is probably Graham Greene's "The Heart of the Matter" Graham Greene was a spy as well, so it's a perfect novel for 007 to read on his flight to Zanzarim.

Many thanks to Ben Williams, and Anders Frejdh. Stay tuned to MI6 for the third part of the transcript.