|

| |

MI6 caught up with Academy Award winner Norman Wanstall

to talk about his career as an editor and his

work on the James Bond series...

|

|

Norman Wanstall Interview (1)

7th February 2008

How did you get started in the film

industry - had you held many jobs before entering the

movie business?

In 1949 I was a 14-year-old schoolboy, and I had a friend

whose mother was the assistant to the Production Controller

at Pinewood film studios. During the school holidays she

invited a group of us to visit the studio and I was absolutely

captivated by what I saw. The highlight of the day was being

allowed onto one of the stages and watching Alan Ladd rehearsing

a scene for the film ‘Hell Below Zero’. The set

was the cabin of a ship and it looked totally realistic,

but of course when we looked around at the back it was all

made up of plywood and scaffold poles. The whole thing was

make-believe and we loved it. It was a magical day and the

memory of it stayed with me right through my schooldays.

After leaving school I spent two years doing my National

Service, and when I returned to civilian life I contacted

the lady at Pinewood and fortunately she remembered me.

She invited me to the studio for a chat, and soon afterwards

offered me a job as a trainee film editor.

|

|

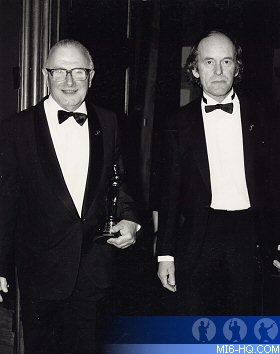

Above: Norman Wanstall with his Academy

Award for Sound Editing for Goldfinger |

I jumped at the chance to work in the industry although at the

time I had no idea what a film editor’s function was. I

was put under contract for three years and by the end of that

term I had moved up the promotion ladder and was the assistant

to one of the sound-track editors (known as dubbing editors.)

I should point out that in those days (and for many years afterwards)

film studios were basically factories. All the producers, directors,

technicians, plasterers, carpenters, electricians and office

staff were all permanently employed under contract, including

some of the leading actors, and everyone turned up for work every

day and went from one film to another. There were of course people

who had left the studio system to work freelance, and they would

invariably work in the studios on films brought in from abroad,

or on independent films brought in from outside. It has been

said that the studio system suffered from bureaucracy and therefore

there wasn’t much scope for innovation and experimentation,

but many fine films were made under the studio system and only

after a technician had received a thorough training were they

ever considered for promotion.

Probably the most accomplished and famous dubbing

editor at that time was Winston Ryder, who had worked on numerous

major

movies including such prestigious tiles as Lawrence Of Arabia

and Bridge On The River Kwai. Just as my 3-year contract at Pinewood

was coming to an end it became known that Ryder was looking for

a new assistant, and

my colleagues at the studio suggested I would be the best man

for the job. I subsequently left to go freelance and worked with

Ryder on three major productions, the last of which was Sink

the Bismarck edited by Peter Hunt.

How did you get involved with Bond and who did you work

most closely with on those productions?

In spite of working extensively on the sound-track side of

editing my ambition was not to become a dubbing editor but a film

editor, so I asked Peter Hunt if he would consider me for a job

as his assistant so that I could return to working with picture

again. He took me on and we formed a good working relationship,

and after four pictures together Peter was given Dr No to edit.

The rest, of course, is history! The budget on Dr No was such

that the production could not afford the two dubbing editors required

for such a busy sound-track (one for dialogue and one for sound

effects) so Peter promoted me to sound-effects editor and I continued

in that role for the next four Bond pictures.

Even though Peter and I were still very much a team, I was left

alone most of the time to concentrate on the assembling and creating

of the sound-effects. As soon as shooting was completed I worked

closely with the production sound recordist, going out with his

crew to record the cars, motor-cycles, helicopters, autogyro

etc. After that I teamed up with the studio sound mixer (Gordon

McCullum), and together we created at an early stage many of

the more complex sounds that involved mixing various components

together.

Above: "This is one of

my favourite pictures taken with the great Gordon McCullum

who was the chief dubbing mixer on the first Bond movies.

He and I worked very closely together creating the specialised

sound effects, such as the electronic sliding doors, Oddjob’s

flying hat and Dr No crushing the metal idol in his clawed

hand. He was a very difficult man to work with but he loved

the Bond movies and couldn’t wait for me to take

tracks into his theatre for him to blend together." |

|

You've had a spell as both an editor

and a soundtrack editor, can you describe the responsibilities

of both, how they compare, and which task do you prefer?

Even though I had a fair amount of success as a dubbing

editor my sole ambition was to become a film editor. The film

editor has so much more influence on the final outcome of the

picture. Usually he comes onto the payroll prior to shooting

and would discuss with the director any concerns he has about

the script. If, during shooting he feels extra shots would

enhance a scene, he would inform the director and if time allowed

the director would shoot them.

From then on the editor is left

alone to put the film together the way the director envisaged,

and once the film is finally assembled (usually a week or

two after the completion of shooting) he and the director

will

discuss each scene and decide where the film could be improved

by making changes or trying new ideas.

You have to remember

that because scenes are often shot from beginning to end

from many different camera angles, the director on a

major feature

film such as a James Bond would shoot hundreds of thousands

of feet of film. The final film that’s shown in the cinema

would only be around thirteen thousand feet long, so you have

some idea of the editor’s job in creating the best possible

movie out of so much material. |

You can see from the above that the director relies very much

on the skill of the editor to get the best out of his material,

and the editor has the satisfaction of knowing that the final

look and pace of the film is very much his responsibility. It’s

a fantastic job and commands a lot of respect from the rest of

the crew, and I know that on all my film editing jobs I was able

to contribute ideas and make my mark in some way. I must say

I was very fortunate during the time I was working as Peter Hunt’s

assistant, because he was only really interested in ‘fine

cutting’ scenes where every cut had to be timed to perfection.

He found the job of roughly assembling the scenes rather tedious,

so he frequently let me put scenes together and then he would

take over later to do the serious work. This gave me a lot of

editing practice at an early stage so I was well prepared when

my big break as a film editor finally arrived.

As regards the job of the soundtrack editor,

I’ve realised over the years that people outside

the industry do not understand that the picture and sound

are totally separate throughout the making of a film, so

they cannot easily comprehend what the job involves. Perhaps

it would be helpful if I briefly explain the way a film

is processed...

The first thing to remember is that the camera and sound

crews are totally separate during shooting, and at times

the sound recordist will be on the opposite side of the

set to the camera. They are linked electronically for synchronisation

but otherwise they work independently. At the end of each

day’s shooting, the negative taken

from the camera is sent to the laboratories and the tape

from the sound recorder is sent to the sound department.

The following day the positive picture comes back from the

labs, and the sound-track comes back from the sound department

transferred onto 35mm stock. The cutting-room staff then

synchronise the two, and every roll is stored away in two

cans, one sound and one picture.

|

|

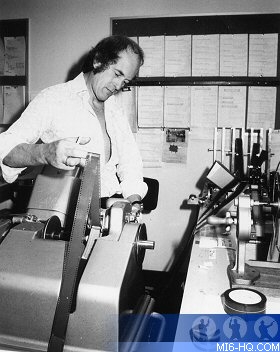

Above: Norman Wanstall in the cutting

room |

By the

time the editor has made his first assembly of the picture (known

as the rough cut) there would be about 13 or 14 cans of film

and the same number of cans of sound. The dubbing editor is able

to assess each reel of sound in turn and decide which sections

of the track can be used in the final

film. In major action films such as the Bond movies, a very large

percentage of the track has to be discarded and re-created from

scratch.

This involves re-recording all the different elements and mixing

them back together again, so even a simple scene of two people

talking as they walk along a street would involve replacing the

dialogue, the sound of their footsteps and movements, the exterior

atmospheres and the sound made by any other items that appear

in the scene. One could easily end up with six to ten tracks

for that one scene alone so you can imagine what is involved

in replacing a battle scene or a car chase. The Bond's were a

lot of work for me because all the boats, trains, planes, cars,

motor-cycles, helicopters, autogiros, gadgets and underwater

sounds etc. had to be re-recorded and replaced from scratch.

Also I had to invent sounds for special-effects scenes such as

the laser beam, Oddjob’s flying hat and the atomic machine

in Dr No’s laboratory. Yet again of course many of the

actors used in the early Bond's such as Ursula Andress and Gert

Frobe were foreigners with strong accents, so they had to be

re-voiced and all the scenes they were involved in had the sound

replaced.

I must say that as a sound-track editor I was

very fortunate to have the Bond's to work on because at least

I could make a

genuine creative contribution at times, but generally the job

is relatively routine and cannot compare with the close involvement

of the film editor.

Which have been your most memorable production thus far?

The

film I worked on that I call my favourite was without doubt Ipcress

File on which I worked as sound-track editor, but my

most memorable film has to be the first film I edited which was

called Joanna. Whilst working on the Bond's I was contacted by

a popular singer/actor/writer called Mike Sarne, who had shot

a short film called Road to St Tropez but hadn’t been able

to afford a sound crew. I liked the guy so much I put a track

on the film for him free of charge, and as a result we became

close friends.

Some time later he was given the chance by 20th Century Fox

to direct his own script (Joanna) and he rewarded me by giving

me the chance to edit it. It was a swinging sixties story and

was unfortunately panned by the critics, but with Mike’s encouragement I’d

applied a very stylised type of editing which was rare in those

days and it got me noticed. The critics picked up on it and other

directors became interested and even the great Norman Jewison

flew me back from Denmark for an interview and short-listed me

for Fiddler On The Roof. Without doubt Joanna was my most memorable

project because it was a huge stepping stone in my career and

enabled me to follow

my ambition of becoming a respected film editor.

Related Articles

Norman

Wanstall Interview (3)

Norman

Wanstall Interview (3)

Norman

Wanstall Interview (2)

Norman

Wanstall Interview (2)

Bond

Music Articles

Bond

Music Articles

Many thanks to Norman Wanstall. All pictures courtesy Norman

Wanstall.