If I Were Prime Minister

21st November 2013

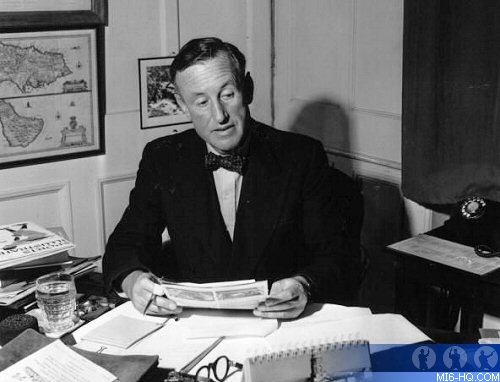

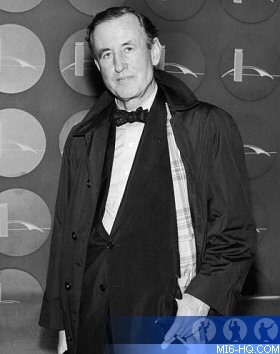

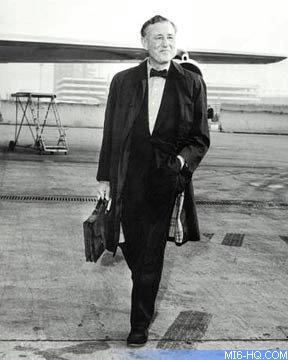

James Bond creator Ian Fleming was, in some ways, years ahead of his time when he penned his political manifesto in 1959

By MI6 Staff

By MI6 Staff

James Bond creator Ian Fleming may have ruled the world of spy literature at the zenith of 007's popularity, but what he he ruled a country? Fleming penned a manifesto, titled "If I Were Prime Minister" for The Spectator magazine after the publication of his seventh novel 'Goldfinger'. Printed in the October 9th, 1959 issue, some of his opinions were years ahead of their time such as electric cars, relaxed gambling laws, a crack down on expenses account abuse, and open access to government figures and statistics.

|

If I Were Prime Minister, by Ian Fleming

I am a totally non-political animal. I prefer the name of the

Liberal Party to the name of any other and I vote Conservative

rather than Labour, mainly because the Conservatives have bigger

bottoms and I believe that big bottoms make for better government

than scrawny ones. I only once attended a debate in the House

of Commons. It was, I think, towards the end of 1938 when we

were unattractively trying to cajole Mussolini away from Hitler.

I found the hollowness and futility of the speeches degrading

and infantile and the well-fed, deep-throated ‘Hear, hears’ for

each mendacious platitude verging on the obscene. If this is

politics, I reflected, I would much rather not see it happening

and I swore never to re-enter the Chamber. I never have.

My own particular hero is Sir Alan Herbert, an independent-minded though admittedly think-shanked man, who swimming alone, stayed out of the muddy red and blue stream and more or less single-handed changed a section of our law for the benefit of the common man. And of course I have the affectionate reverence for Sir Winston Churchill that most of us share. But in general I regard politicians as a race apart and if the Bottle Imp were to offer me high office I would accept, and that with reluctance, nothing less than the Premiership.

|

On taking office, I would concentrate on small things. The big things—the H-bomb, the conquest of outer space, the colour problem—these are too vast and confused for one man’s brain; I would leave them to my Ministers and to the wave of common sense, which, it seems to me, by a process of osmosis between peoples rather than between politicians, is taking a rapid and healthy control of the world. My first ‘Action This Day,’ through my Minister of Transport, would be simple but significant: on the road signs displaying a diamond-studded black banana with the word ‘CURVE’ underneath, I would have the word ‘CURVE’ removed. By this and other small tokens, I would proclaim that the English people are no longer babies and that, after all these years of universal education, I propose to deal with the citizens as if they were in fact universally educated. All my education would start with this assumption. |

|

Next, I would try and stop people being ashamed of themselves. In the United Kingdom we have a basically nonconformist conscience and the fact that taxation, controls and certain features of the Welfare State have turned the majority of us into petty criminals, liars and work-dodgers is, I am sure, having a very bad effect of the psyche of the kingdom. Tax-dodging in all its forms would have my attention and I would proceed to reduce income tax, surtax and death duties by the maximum amount possible in exchange for abolishing all expense accounts and other forms of fiscal chicanery. Motor-cars, whether Rolls-Royces or Fords, owned by a company, would have the name of that company displayed in half-inch letters in a prominent position so that if a company’s car was seen disgorging a load of mink and cigar smoke in theatreland in the evening, any of the company’s shareholders who happened to be a witness could, if he wanted, ask the company to justify the use of a company vehicle. But the real deterrent would be snobbery. I think everyone would gain morally by this legislation and no real harm would be done to anyone. To begin with, of course, the restaurants would suffer from the absence of the expense-account aristocracy who have ridiculously inflated the price of meals all over the world, while at the same time deflating the quality of the food. I would hope that the really good restaurants would survive, but that the hosts of bogus eating places with Algerian ‘Infuriator’ (otherwise known as ‘Instant’ Burgundy), described as Beaujolais selling at 15s. for half a carafe, would disappear.

Having looked after the moral fibre of the ‘Haves,’ I would next direct my attention to the work-shy ‘Have-nots,’ being convinced that the man who is not returning good work for good money is basically ashamed of himself. In consultation with the trade unions, I would devise a scheme of benevolent Stakhanovism. There would be a minimum wage in every industry, but rapidly mounting merit bonuses for real work in either quantity or quality. This would not abolish tea breaks or the games of whist but make them unpopular with the wives. I would also request the trade unions to re-examine the whole question of overtime. Having obtained an eight-hour day and a five-day week, it seems to me wrong that workers should use two extra days and many extra hours earning overtime double money when they should be enjoying the leisure and repose they have fought to obtain.

And while on the subject of leisure, I would certainly consider appointing a Minister of Leisure, with a small staff, to make every effort to enhance the pleasure people get from their increasing spare time.

Having observed at close quarters the great waste of money on paint and canvases in one of our art schools, I am not convinced that the Welfare ‘artist,’ copying as he usually does, one or another, or very often several, of the modern theories of painting, is worth encouraging any farther. Instead, therefore, of spending larger sums on the arts, I would spend them on the crafts. I would encourage the fine metal workers, enamellers, binders, printers, woodworkers, etc., in a most lavish fashion and attempt to arrest at once the decline of the craftsman, even down to the lowly thatcher.

|

To give the craftsman, the designer and, of course, the artist an outlet for his capabilities, I would take the Rolls-Royce motor-car as an example and persuade all manufacturers that, let us say, 5 per cent. of output should consist of an absolutely top-grade, luxury product in which price is an entirely secondary consideration. Every firm would then be producing, perhaps only in small quantities, the Rolls-Royce of its particular line of manufacture—real grain whisky and gin, quintessentially distilled, ice-cream made with real strawberries and real cream, lavatory paper as luxurious as a peach skin, scissors that actually cut your nails, and so on through the list of all our products. By this means I would make quality goods available to those here and abroad who like these things and can afford them and I would hope to educate the admass to eschew the shoddy. Coincidentally, in the world’s markets, ‘British made’ would go back to the place where it used to belong. |

|

Next I should proceed to a complete reform of our sex and gambling laws and endeavour to cleanse the country of the hypocrisy with which we so unattractively clothe our vices. To deal only with my most far-reaching proposal, I would consult with my Minister of Leisure about the possibility of turning the Isle of Wight into one vast pleasuredome (cf. Fr. Baisodrome) which would be a mixture of Monte Carlo, Las Vegas, pre-war Paris and Macao. Here there would be casinos (they are building one on Gibraltar and they have one in Nassau; why not one on the Isle of Wight?) and the most luxurious maisons de tolérance in the world. Bingo, poker, faro, fan-tan, craps—even whist drives with money prizes! This would be a world where the frustrated citizen of every class could give full rein to those basic instincts for sex and gambling which have been crushed through the ages. At last our cliff-girt libido would have an outlet and the sleazy strip-tease joints, rump-sprung street-walkers and backroom card games would be out of business forever. Since it is impossible to suppress the weaknesses of mankind, I would at least put an honest face on the problem and do something to release the homme moyen sensuel, or femme for the matter of that, from some of their burden of shame and sin.

After dealing with the spiritual comfort of the electorate, I would proceed to his physical state, and my first step would be the abatement of noise, carbon-monoxide gas and exasperation caused by the traffic problem in our big towns. I would solve these with the help of Mr. Francis Bacon’s recently invented, much-publicized battery. Our present internal-combustion engine is a ridiculous steam-age contraption which turns only a modest proportion of fuel into energy and spews the rest out in the form of petrol vapour of a more or less solid consistency. When there is no wind, this lies in a dense layer in our streets and we breathe it in day and night. It then rises into the upper atmosphere, where I am told, it forms a kind of envelope round the world which has the effect of interfering with the beneficial rays of the sun. Whether that is so or not, the petrol engine is obviously a noxious and noisy machine, and I would gradually abolish and replace it by some form of electric motor. This would take some time, but I would hope that, within three years of assuming office, I could have converted the whole of central London to electric transport. Very cheap, State-owned garages would be built at the point of entry into London of our main roads and drives would there transfer into electric buses or the Underground and later into cheap, State-run electric taxis. There would be quiet, no smell and no parking problems. Gradually I would extend this system to our other great towns and in due course the problem would be solved for the whole country.

|

In an attempt to make government more honest, I would face up to the fact that my Exchequer battens fatly on the vices and follies of the electorate and I would have HM Stationery Office publish quarterly a periodical entitled Hazard. Hazard would give, without comment, the very latest information obtainable anywhere in the world on the ill-effects of smoking too much, drinking too much and consuming white bread, TT tested milk, refined sugar, foods too long frozen, etc. Hazard would also give the correct odds for football pools and Premium Bonds and, from time to time, publish the annual accounts of the bookmaking firms throughout the country. Road accident figures would be given in detail, and in cases where mechanical failure (those shattering windscreens, for instance) attributable to faulty manufacture was involved, the name of the manufacturer would be published. There would, as I say, be no editorial comment in the magazine, but I should be able to face with a clear conscience the fact, from the Exchequer’s point of view, the most valuable citizen is the man who drinks or smokes himself to death. |

|

There are other various small matters I would attend to, such as men’s clothing, which I regard as out-of-date, unhygienic and rather ridiculous; press reform—we have the grimiest press in the world; the matter of titles—I would greatly reinforce the Orders of Chivalry and, if a Lord or a Baron or an Earl did not behave as a lord or a baron or an earl should, he would lose his title after the third offense (as is more or less the case with Service rank); rich State prizes for all inventions or innovations that were even of remote benefit to the Commonwealth; enthusiastic encouragement of emigration, but more particularly of a constant flow of peoples within the Commonwealth; a Commonwealth super-Parliament; and less fried food for the constipated masses.

All these, as I have said, are small, workaday things—too small, alas, for the attention of either Mr. Harold Macmillan or Mr. Gaitskell. So I look forward, with squared shoulders and glazed resignation, to five years of Summitry, pensions and the 11-plus.

Thanks to MI6 Community member 'Revelator'.