|

| |

MI6 recently caught up with sound editor Colin Miller

to talk about his work on six consecutive James Bond

films in the '70s and '80s...

|

|

Colin Miller Interview

2nd March 2009

MI6 recently caught up with sound editor Colin Miller to talk

about his work on six consecutive James Bond films, from "The

Spy Who Loved Me" to "The Living Daylights"...

How did you get started in the film industry and what lead

you down the path of a sound recordist?

I joined a company called Pearl

and Dean – who used to

make cinema commercials – as a runner in the cutting rooms

and animation department of Pearl and Dean. I was there for three

years and went away on holiday and came back to be told that

the entire editorial department had been fired due to internal

policy. Now, it wasn’t just the editorial department, it

was a few other departments as well. There was a commercial company

based in Shepperton studios who were looking for an assistant

editor for a month.

Of course I grabbed that: I went out to Shepperton studios and

began working at the company called Anglo-Scottish for this month’s

holiday-relief and stayed there for three years and got to meet

various people who were working on feature films. One day I got

a call from a feature film editor saying that he was just about

to start at film and was

looking for an assistant and had been given my name. I took

the job as an assistance editor on "The Valiant" and

here I am today.

|

How did you end up working on your first James Bond film,

The Spy Who Loved Me?

I’d been working on a number of films with a sound editor by the name

of Derek Holding – he was a dialogue editor. We’d just finished

a film and Derek went off to join "The Spy Who Loved Me" as a dialogue

editor. When they needed another sound editor Derek was kind enough to put

my name forward. I went for the interview and got the job. I came a little

bit later in the process and quite a bit of the work was already done. So,

hence there is not credit for me at the end of the film, but I was on it for

a while.

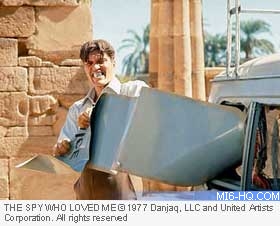

For your work on "The Spy Who Loved

Me" – can

you describe one of the sequences that you were involved

with and what exactly your job entailed?

One of the scenes takes place in the desert, when Bond is in the van and trying

to escape but is caught up by Jaws. It was the trip across the desert. That

sequence was shot without any sound whatsoever. Now I had done another movie

involving a rather ancient vehicle. So, Alan Sones used my recording for the

van. It was then my job to apply the sound effects around it. So basically,

he did all the mechanical work and it was me who applied all the smashing of

things by Jaws. |

|

|

Another example is the Lotus

Esprit underwater – dreaming

up sound effects for things like the motors and the steering

or making the frog-men noises sound really genuine. A lot of

editing took place to make sure the timing was all correct. There’s

always the famous chase between the girl in the helicopter and

the Lotus Esprit– that was great fun to

do. As luck would have it, they did have a sound unit covering

a lot of the action. So, a lot of the helicopter stuff that was

shot was used. It was a matter of taking the various elements

and synchronizing those shots. Of course there was the shooting

and gunning of the Lotus and the eventual destruction of the

helicopter.

How long would an average sequence take you – depending

on the complexity?

Some sequences are

quite short while others are perhaps longer cuts. So, you might

spend, on a two minute sequence, 4 or 5 days depending on the

complexity of what you had to do. Because, you see, so many of

the Bond movies have multiple units that intercut and what have

you, and some of the 3rd or 4th units didn’t have sound.

So we have to find that sound and ease the joins into areas that

did have sound. So, this is all part of the creativity.

How did you end up working on the next Bond picture, "Moonraker"?

Well,

a team had been created on "The Spy Who Loved Me" and

it was the same team that was brought back again.

Did you move to France to work with the rest of the production

there?

No, what happened was that the shooting was all being done

in the studio in Paris. The editors were over there but Alan

Sones and myself were based in Pinewood studios. The editors

would cut sequences in France and send them to us. We would then

do our work and do a small dub on those sequences. We would then

do day-trips to Paris with our dubbed sequences, take them to

the editors so that they could continue their work. So, we were

to and from Paris on day trips, during the final shooting process.

|

|

|

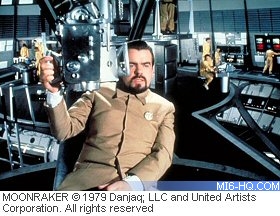

"Moonraker" is one of the slightly more abstract

Bond films, being in space and other slightly different

environments. Can you tell us how you went about creating

the sound for these different environments?

Well, the thing about "Moonraker" is that it was a huge challenge

in as much as you say: there were just so many changes of location. For a lot

of the effects, in those days there was a very good library that we were free

to draw upon. So we could look at a sequence – and in most cases we had

access to a large collection of effect from previous Bonds. As you probably know,

there is quite a bit of repetition in the Bond films, they always had their favourites.

But any new sequences or scenarios we’d then have to record ourselves or

we would go to the sound library, bring it back and apply it to a sequence.

Brazil was a particular challenge because of the shooting

of the Mardi Gras. Now they did have a sound unit there,

as it was all part of the main unit, so they did cover

a lot of the carnival. We had this material to draw from.

The chase through the Brazilian river was partly library

sound effects and partially sound that was shot during

the sequence. Then we added all the funny gadgetry noises

that went with it. |

When it came to the space station – now

that was our particular challenge. The huge great mission control

was absolutely great

because we had to create a lot of the technical dialogue. There

was a NASA technical advisor on the film but he was actually

able to give us the exact technical details, but in some cases

we had to polish it up to make it a little more "filmic".

For instance, the helpers that were in the space complex, they

needed a name for them – so I came up with an "astro-technician",

and these are the kinds of things that become part of our creativity.

It was very exciting finding the proper sound effects for this

great rocket that is launched into space and then we had to create

all the various sound effects for the space station itself. But

the biggest challenge here was the big battle in space – because

as we’re all aware there is no sound in space. Of course,

this is no good for a Bond picture. Stanley Kubrick pulls it

off very well in "2001: A Space Odyssey", but of

course that is his style of filmmaking.

|

There were various guns that were used – the

pistols, the riffles and the cannons. Now nobody knows

what one of these sounds like so we had to put our thinking

caps on. I suggested we needed something like a synthesizer,

so we went to the office and they found this famous record

producer who had a synthesizer. So, we went to his recording

studio and I think it was CTS studios in Wembley. Before

this we had brought the guy down to our studio and we showed

him our sequence and these short stabs of light from these

pistols and riffles and cannons and we said "this

is what we have to come up with." So he started to

play around with the keyboard until we found sounds we

liked for each gun. We recorded a collection on individual

sounds, about 50 of each, all slightly different lengths.

Now remember that each shot had to be cut and assembled

individually and if you look closely at the film you’ll

see this sequence has a lot of short, sharp shots and so

this meant an awful lot of work. Still, at the end of the

day, it worked very well.

Can you tell us about the sound effects

and atmospheric sounds used on the space station?

We just had to use our imagination, coupled with some technical excellences.

We took our own head there and experimented with things. |

|

|

As you know the space station is very

big and very active and to find the right kinds of sound effects

for the environment we drew on NASA material that was made available

to us – in terms of background noises. From there, we built

our own atmosphere on top of those. So we created a bed of natural

sound and added our effects on top of that.

How did the "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" motif

end up in the final cut?

That was done through the office. They

negotiated with Spielberg’s

company for the use of that and eventually they got to use it.

It was such a great trick of the time and everybody thought, "well

if we can pull this off it would be great".

|

|

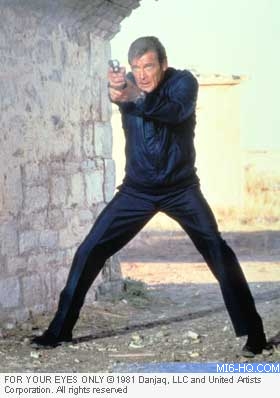

In "For

Your Eyes Only", a more simple approach

to filmmaking is taken. How did you reflect this change

in the sound editing?

A lot of things are set within the Bond picture. You are more or less following

a line, just making variations of this line as you go along. That’s the

best way I can describe it. It was more, as you say, a conventional Bond movie,

there was nothing so challenging as "Moonraker". There were just

a few things within it that were challenging.

There was that car chase with the Citroen – that

was great fun to do. A 3rd unit shot the whole sequence,

I think, totally without any sound whatsoever. I then had

to go out with the stunt man one very cold November day,

and we recreated that chase. The thing about that was the

fitted out car sounds totally different to just a 2CV engine

that’s normally in one. By re-recording it with the

stronger engine, we made it much more dramatic and much

more fun. Of course with Carol

Bouquet driving we had screeching

and crunching of gears to apply. It was those kind of things

that made it all so exciting. |

When John Glen moved out of the cutting room

to direct the film – how

did this effect the team that had been put together in the earlier

films?

The team that had been working with

John in the previous films all sort of moved up one place. John

Grover

who had been working with Glen as an associated editor was sort

of elevated up to become the editor under John’s direction.

|

One of the more interesting sequences in the film is the

underwater sequence. Can you talk us through what this

involved?

It was a big challenge trying to get reasonable sound quality of genuine underwater

sounds was a bit of a challenge at that time. But we went along to several

sound effects liberates and even in the studio we were able to create reasonable

sounds for underwater. Once again we were back with our frogmen and underwater

spears. But each of the Bond underwater sequences has a new concept we have

to address.

What do you remember most about your work on "For

Your Eyes Only"?

The thing about it is the creativity itself. I think in "Moonraker" there’s

only about 15% of it was original sound – all the rest was made up. You

were re-recording all the dialogue where for technical reasons the recorded

sound was unusable. Perhaps because of dummy explosions or assistant directors

shouting over actors doing their lines. Or if the actor is doing something

at the time – like firing a gun or simply running. We have to find the

sound effects. All these things are blended together. |

|

|

As a sound a sound editor, you involved in the final mix of

a film. What is the process and how long does it take?

Yes, as a sound editor, we are totally involved. So, generally

what happens is

that once we’ve prepared our tracks we go into the dubbing theatre with

the dubbing mixer and on our own. Generally on a Bond picture the editor edits

sequences together and sends them to us to mix a rough track over the top. This

way people can say, "we like this sound but we don’t like that one." So

when we go into the final dub a lot of the elements of a sequence are already

known, so it is left to us to "premix" – we take all these

elements, and under our guidance (having known what the editor and director require)

we mix these all together. We do the dialogues first and then we run the dialogue

mix and premix the effects against this. Then we come to the foley sound effects

and the same process occurs.

So, by the time we come to the final dub a lot of the aspects

have already been premixed. At this time we call the director

in and we sit down, work our way through the reel with the comments

coming from the director, editor and sound editor.

Can you talk us through the process of looping?

The looping process

happens whenever the sound from a shoot is unusable – perhaps

you get people talking on location, or perhaps one angle is particularly

noisy or the artists might

be speaking so softly. So when you’re cutting from angle

to angle, the sound levels will jump up and down and what we

have to do is decide if we can save it and smooth it out in the

cutting room, or if it has to be re-recorded again. In the case

of the Bond films it almost always has to be done again as there

are many technical problems associated with it. So, we have to

run the film in the cutting room and write down the text where

the first modulation of the first sentence begins – giving

an in-point and an out-point and we get this all typed up. We

then go into the recording studio with the artists. We run the

sequence and say "this is what we need to do" so

that they appreciate what has to be done. And they re-perform

the line as close as they can under the direction of the director

and the sound editor. Whole sequences are done like this and

its it the dialogue editors job to go through these recordings

saying "we want this

bit from take one and this bit from take two".

|

|

Can you tell us about dubbing the actors voices and any

stories from the dubbing process?

Well, I was mainly involved with the recording of the sound effects and my colleague

Derek Holding was responsible for the recording of the principal artists. I have

been to many dubbing sessions myself, but not on the Bonds. "Q",

bless him, never got into post sync and because he was such an aged gentleman

by that point, he never knew what it was all about. But, bless him he did try.

Roger, of course, only has one way of doing – and that is Roger’s

way. So if there’s something wrong with the sequence or he sees something

behind him he’d just ask to run the sequence again. Grace

Jones was interesting,

but a little bit feisty: "what are we doing?", "can’t

we use the original here?", "do I really have to do it?" But

that just was Grace Jones.

Can you talk us through creating an atmosphere for the

underground mine in "A

View to a Kill"?

That was nearly 100% replacement as during nearly all those scenes. The director,

or assistant director, would be shouting through a megaphone, directing all

the action. The other reason being that, because it was shot on the 007 Stage – which

is not designed for shooting sound – therefore the acoustics were terrible

and everything had to be replaced in that mine sequence. |

Particularly things like the miniature railway. Because so

many of the scenes were covered by about 5 cameras, the sound

department

couldn’t get in close – so was like a general sound.

But as you see in the final cut there’s lots of changes

of angle and close ups. So I had to go in at the end of the day’s

shooting with a sound recordist and having seen the shots that

had been cut together, run the train just in sound form to cover

the new shots for the picture.

|

How did you record the sounds for the

air-ship that featured in "A View To A Kill"?

That was one of my best days ever! I was given an Air-Ship

500 for a day to play with. So we went to RAF Cardington,

which used to have airships just before

and after the war.

What we did was to pull two pilots into

the cutting room and ran the sequence for them, explaining

what we wanted to do. A few days

later, my assistants, my sound recordist and I went to Cardington where we

explained what we’d like to do first – but the problem we had here

was that we couldn’t use Radio Mics as they would be picked up on the

recording.

So what would happen was that we’d have the air-ships

hovering above us at about 100ft and talk on the radio

to the pilot. I would send them off and tell them that

I would direct them by waving my arms around. So, I looked

like a manic air traffic policeman. So they’d come

at us like a man machine and I’d suddenly whirl my

arms around to indicate that this was the part that they

gun the engines and they’d turn around us, or come

up and stop. |

|

|

Having captured all the external audio they’d come down,

pick us up and then we’d do exactly the same stuff, recording

from inside the cockpit. It was a wonderful noise. If I remember

rightly, it was a pair of Porsche engines and it made the most

wonderful noise. From there, it was my job to go back to the

cutting room and make it all work. A memorable day out – one

of many on the Bond movies.

With the introduction of a new Bond in "The

Living Daylights",

was there a new sound also?

No! The only thing that changed was

Bond. There was a repeat of the generic noises we’d heard

before. The only thing different was the scenarios.

Of all the films you’ve worked on to

date, of which are you the most proud?

Of the Bonds, I’d have to say "Moonraker"!

I was not the supervising sound editor, but I must say that I

was very pleased with my work on the film "The Adventures

of Baron Munchaussen" – I was the dialogue editor

on that. Once again, that was a hugely challenging movie.

Many thanks to Colin Miller.