Exclusive Extract

9th May 2023

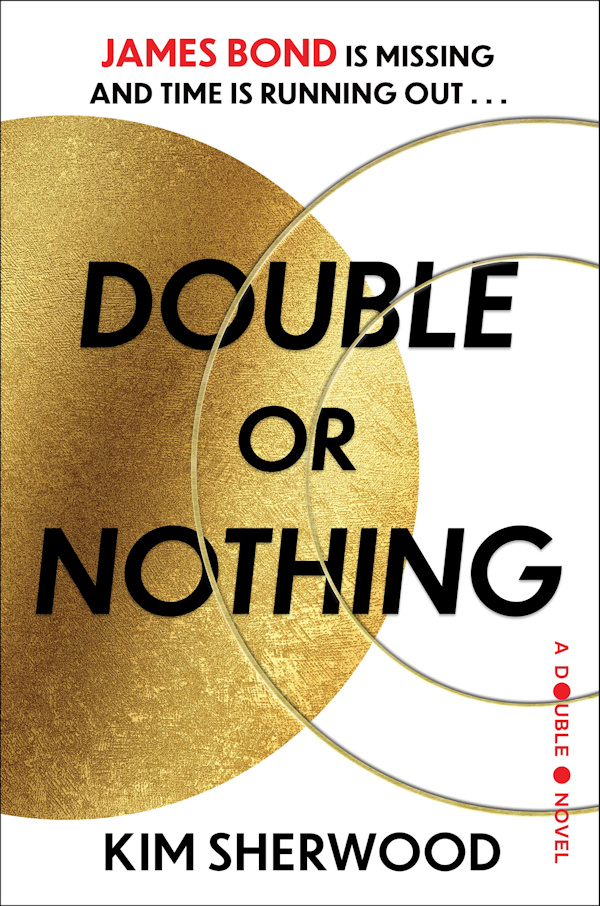

Read a chapter from the new novel 'Double Or Nothing'

By MI6 Staff

By MI6 Staff

Excerpted from Double or Nothing by Kim Sherwood. Copyright © 2023 by Kim Sherwood. Reprinted courtesy of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

4. Blank Sun

The security officer who presided over the lifts of the Regent’s Park office was a navy veteran called Bob Simmons who rested the stump of his left arm against the panels only he could operate. He could read the building like few others. When a Double O stepped on at the basement, he would sniff the gun smoke on them, and either congratulate or commiserate on their score that day in the shooting gallery. He was always right. When the doors sighed open on the eighth floor, the offices of the Double O Section, Simmons could tell from the pace of activity in the corridor—whose drab Ministry of Works green had long outlasted the ministry—whether a crucial flash meant good news, or loss had thrown its shroud over the screens. When 008 had been killed in the field last month, the floor was muted. No one on Moneypenny’s staff let doors swing open, or bang shut. It was as if they had all agreed to a minute’s silence that would not end.

Simmons had only recently grown accustomed to thinking of the office on ninth as Moneypenny’s domain. Sir Emery Ware was mostly based these days at SIS HQ on the Thames—M described the building as a bureaucrat’s Aztec temple stranded in Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens—and he always hummed in the lift whenever he was called back to his Double O’s. Simmons knew that was how M still saw the Double O Section, himself the only Double O to survive the racket, granting him legendary status and the crown, first as Section Chief and then M when his mentor Sir Miles Messervy retired. He’d over- lapped with 007 and Moneypenny in their first years in the Section, introducing Bond to all brands of fun trouble, all the while telling Moneypenny he was giving her the gift of experience as she fished them out of it. Sir Emery appointed Moneypenny as Section Chief when he moved to Vauxhall to become Chief of MI6. But he’d never let go. These vainglorious but effective weapons were his children.

Today, Simmons felt the good news in the straining cords of the lift as staff came in and out, carrying word from floor to floor, though the message would have crossed every station already. This was news to share personally, a moment to savor. Regent’s Park had been living under a cloud for more years than Simmons cared to count. The original 009 was shot on a job. 0011, Harry Mace, disappeared on assignment in Singapore. Elizabeth Dumont and Anna Savarin, 002 and 0010, were killed in Dubai and Basra. 005, Ventnor, had fallen to his death while on a mission with 000, Harthrop-Vane, or Triple O as he was dubbed. 000’s wrist and fingers remained bruised for weeks, a souvenir of his efforts to pull Ventnor to safety. Add to that the day Bashir limped in without 007 at his side. He did not meet the security officer’s eyes. Bob understood Bashir and Harwood split up after that. But today, finally, some good news. 009 had brought 003 back home.

Simmons rode down to the garage, and stood to attention without quite realizing it as the doors whispered open. He looked past the Aston Martin, which remained under dustsheets, to Harwood’s Alpine A110S in matte thunder gray, expecting to hear its 1.8-liter, 4-cylinder, 16-valve turbocharged engine easing to an echo. But the car was just as quiet as the DB3. Instead, there was the hiss of Ms. Moneypenny’s Jaguar E-Type, whose quiet electric engine Simmons thought of as almost indecently spy-like.

Moneypenny pushed the door to with her elbow, waving at Sim- mons over the bonnet of the car. Simmons saluted.

“Ninth, please, Bob.”

“Ma’am.” He touched his fingertips to the panel, and a set of symbols only he understood glowed briefly, then disappeared at a tap. She stepped on beside him. Simmons tried to detect any sense of satisfaction from her, but her cool stare was as direct and quizzical as usual, with no spark to give the game away. She wore oxblood brogues, gray slacks, a green silk shirt with the gold-and-turquoise insect brooch that Simmons thought she wore when she wanted to get away from here to warmer climes, and an amber trench coat with the collar up, catching her curls, which glistened wet. The splotchy newspaper un- der her arm showed a photograph of Sir Bertram Paradise posing outside his satellite megafactory in Wales. Simmons caught the clench of her jaw. “Rain again?”

“Thirteen consecutive days,” said Moneypenny. “I should have placed a bet.”

“You want to bet on something,” said Simmons, “bet on the sun.”

A small smile. “I don’t think bookies would take a bet on whether the sun will rise.”

“Not rise, ma’am. Whether it will blink.” She glanced up. “Excuse me?”

“The sun is blank. No sunspots for over one hundred days. That’s a record.”

“Does that mean anything?”

“Now is a good time to take risks,” he said, “but don’t be surprised if those closest to you, either at home or in the workplace, deliver a surprise. At least, that’s what my daughter posted on Instagram this morning.”

Moneypenny freed her hair from her collar. “I’ll look into that for her.”

“Obliged, ma’am.”

“Don’t expect 009 or 003 today.” She looked at him sidelong. “I know the building’s humming, but Bashir is due to debrief at Vauxhall, and Harwood is bound for Shrublands.”

“She got seven days without the option?”

“Something like that.” The lift slid to a stop. “Thanks, Bob.”

She turned left and walked past Communications, where sun- spots and the movement of the Heaviside layer used to hold great significance. She made a note to ask the listeners if they ever got any intelligence on the sun these days, and pushed through the green baize door. Her assistant, Phoebe Taylor—a petite young woman with a purple fringe, a smile brighter than the sun, whatever the sun’s movements, and an IQ brilliant enough for Op Management—rose from her seat.

“Morning, ma’am. 009 and 003 have touched down.”

“Thank you.” She looked past Phoebe to the window, the glistening treetops of the English Gardens. “Any word on when he’ll be arriving?”

“Not yet.”

Moneypenny touched her brooch. “Let me know.” She slipped off her coat, turning to find Phoebe waiting; smiling, she let her take the wet thing. Moneypenny opened the door to her office, hearing the hum of the red light go on overhead—signaling she was not to be disturbed—and closed it behind her, resting for a moment against the soundproof padding.

So, Mikhail Petrov, the subject of Bond’s final mission, was dead. Moneypenny crossed to the window, forcing the sashes to relent and let it up by the inch allowed by security. She wanted the smell of rain, wanted to wash the whole place out. Raindrops bounced on the sill and ran to the ground.

She sat behind the glass desk, and tapped her screen. Her fingerprint swelled for a moment across the sensitive surface as if rippling across a pond, and then the crime scene photographs flashed up along with the report. The body in the bathtub. The wet tiles. The complimentary toothbrush glass broken.

Mikhail Petrov was dead, and Anna Petrov was missing.

Her first instinct: tell Phoebe to alert James. She and Bond had grown up in the Service, she as an agent runner in the field, he as the agent she was running. They had performed funeral rites and miracles over old wars and new wars, twenty years fighting nouns concrete and abstract, from drugs to terror; they had been rising stars, first sternly doted on by Sir Miles, then pinned together by Sir Emery to the top of the firmament. James would always be her first instinct.

Moneypenny pinched her fingers over her forehead, minimizing the images of Mikhail’s murder in her mind. She imagined the swing of her door—for James never knocked—and there he’d be. The black comma of his fringe, always a little out of place; the gray-blue eyes that looked back at her with a hint of ironic inquiry; the longish nose; the straight and firm jaw; the slightly cruel mouth, smiling now as he said: “Miss me, Penny?”

She would start, hand to her heart. “Day and night, James, day and night.”

He’d sit down on the corner of her desk. “I hate to think of you losing sleep over me.”

“Especially when it’s so much more fun losing sleep with you,” she’d say, picking up her letter opener and tapping him on the shoulder. “Or so I’m reliably informed.”

A gasp. “Who’s been playing kiss-and-tell?” “Who hasn’t?”

“You know you’ve spoiled all other women for me . . .”

Moneypenny wasn’t sure whether that was an actual conversation they’d once shared, when the idea that James Bond might one day fail to appear at her door seemed impossible, despite his insistence that he would die before the statutory retirement age of forty-five. An age he’d recently passed, refusing a promotion and a desk, in a grudging compromise between fieldwork and training. Why worry about the end, he’d say. Every mission carries a high probability of death. If it didn’t, Penny, you’d give it to somebody else. And the moments when it seems touch-and-go, he’d tell her—they just remind a man that being quick with a gun and easy with a smile doesn’t mean he’s invincible. He might be tarnished with years of treachery and ruthlessness and fear, but what waits in the dark isn’t afraid of him. Why should it be afraid of his cold arrogance and the flat bulge of a Walther PPK beneath his left armpit? There’s nothing to do about it. The whole of life is cutting through the pack with death. If a man makes it home to flirt with an old friend, that comes courtesy of his stars. Better thank them.

And then his stars had failed him. The sun went blank.