Profit Sharing

4th September 2014

Cubby Broccoli was 'shocked and distressed' 30 years ago when Sean Conenry sued him and MGM for $225 million

By MI6 Staff

By MI6 Staff

"Connery Won't Live And Let Die" - 4th September 1984 (Los Angeles Times)

Agent 007 wants his money, and this time his secret service boss "M" can't help him. A $225 million lawsuit was filed by actor Sean Connery against MGM-UA Entertainment Co. and producer Albert Broccoli earlier this summer in U.S. District Court over what Connery claims are his profits due from five of the James Bond movies in which he starred as the British supersleuth.

Yesterday in London, Albert Broccoli, producer of the James Bond movies, said he was "shocked and distressed" at Connery's claim. "The only thing that I have done to Mr. Connery was to place him in the role of 007, which became the most successful film series in the world and made him an extremely wealthy and important film personality," Broccoli said. "My attorneys are dealing with his unfounded allegations."

The federal court suit provides a detailed look at the structuring of the business deals between a popular star, his producer and the company that financed and released the films. It also shows the escalating power Connery wielded in these negotiations as the Bond series became popular. In a fashion typical of today's movie stars who possess negotiating clout, Connery was able to obtain an increasing percentage of, first, the net profits from the Bond movies, and then a share of the actual money returned from the theatres playing the films.

In an unusual twist, Connery's suit, which charges MGM-UA, one of its foreign subsidiaries, producer Broccoli and two of his companies with fraud, deceit, conspiracy, breach of contract and infliction of emotional distress, also accuses the defendants of federal and state securities violations. Connery's contention is that his profit participation constitutes a security, just like a stock or bond, and that by allegedly not paying him all the money he claims is owed him, MGM-UA and Broccoli have violated the strict federal and state securities laws.

Above: Sean Connery with wife Micheline Roquebrune in 1983.

Connery's lawyer, Larry Stein, would not comment on the suit, which was filed June 20. Broccoli is in England making the latest James Bond film, 'A View To A Kill.' Roger Moore now stars in the Bond series, after replacing Connery in 1973 with 'Live And Let Die.'

The lawsuit, filed by Inforex Corp., N.V., a Netherlands Antilles corporation entrusted with collecting all monies due to Connery from the Bond films, concerns the profit accounting on 'From Russia With Love,' 'Goldfinger,' 'Thunderball,' 'You Only Live Twice,' and 'Diamonds Are Forever.' The last Bond film in which Connery appeared, 'Never Say Never Again,' was not produced by Broccoli and was not released by MGM-UA. It is not part of the lawsuit.

The lawsuit says Inforex discovered the discrepancies only in the last two years, "and could not have discovered them earlier." One interesting aspect of the suit is the identification of the many companies Connery employs to provide his services as an actor to a movie production. The days in which a major performer agrees to appear in a film, and then paid directly for that appearance, are long gone.

Primarily for tax reasons, most actors (along with prominent writers and directors) use "loan-out" companies, often incorporated in tax havens such as the Netherlands Antilles or Switzerland, that ostensibly supply their services to a productions. Connery set up different companies to lend him out for each of the Bond pictures, according to court documents.

The relationship among Connery, Broccoli (through Danjaq, a company he owned wit hthe series' original co-producer Harry Saltzman) and United Artists (which was bought bu MGM in 1981) began in 1962 with 'Dr. No.' According to the lawsuit, Connery agreed at the time to five separate options for subsequent Bond pictures.

The first option on Connery's services was exercised a year later, according to the lawsuit, when the actor agreed to appear in 'From Russia With Love.' Although no salary figures are specified in the suit, it shows that Connery was guaranteed one per cent of all gross monies in excess of $4 million received by United artists in the United States.

Court documents show that in 1964, Danjaq agreed to pay Connery five per cent of the profits from all the subsequent Bond films in which he appeared, including 'Goldfinger,' which was released that year.

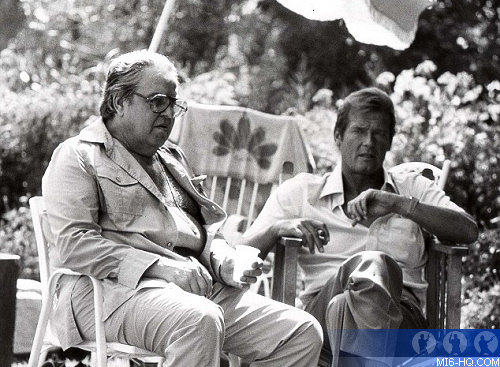

Above: Albert R. Broccoli on set with Roger Moore.

By 1966, the Bond craze was in full bloom. When 'You Only Live Twice' was in productions, the law suit shows that Connery was awarded five per cent of the net profits for his services to Eon Productions, Broccoli's English-based company that made the film, and an additionally five per cent of all profits the film made outside of Great Britain, Ireland and North America. This was a recognition of the Bond films' international drawing power, and an improvement of Connery's deal for a share of U..S-only profits from 'From Russia With Love.'

The law suit reveals that Connery's most significant negotiating victory came when he won 25 per cent of all profits received by Danjaq form the merchandising of the James Bond character and the 007 trademark. At the time, it was very unusual for an actor to share in merchandising rights based on a character he played (this was before the 'Star Wars' merchandising bonanza). Connery also won strict accounting procedures on the calculation of his profits.

By the time Connery's last Bond film, 'Diamonds Are Forever,' was made for Broccoli and UA, Connery seemed indispensable to the production. The lawsuit reveals that his new deal called for him to get 10 per cent of the gross receipts from the first dollar the movie made, rather than a share of the profits. Court documents show that there was a separate agreement covering the United Kingdom and Ireland that gave Connery and additional 2.5 per cent of the gross receipts from 'Diamonds.' That brought his total share to 12½ per cent of every dollar the movie made.

The major thrust of Connery's suit is that neither he nor any of his companies have received any of his profits from 'Dr. No,' and none of the money due to him from the merchandising of the James Bond character. The suit also claims that from March 1979 to November 1983, MGM-UA withheld from Connery's Inforex company at least $300,000 due to him in profit participation from 'Goldfinger,' 'Thunderball,' 'You Only Live Twice,' and 'Diamonds Are Forever.' Connery also accuses the studio of holding $975,000 due Inforex from March 1979 to July 1982 and demands interest on the money as well as its return.

But the most novel element of Connery's suit is his accusation against MGM-UA for securities fraud. The actor claims that the studio violates the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 by misrepresenting the status of Connery's profits and not disclosing their true and accurate status. In effect, he charges the studio with corporate fraud by mishandling his investment, which in this case consists of his services as an actor.