Bond's Brothers In Arms

25th January 2014

Benjamin Welton inspects the mid-century counterparts to Fleming's 007: popular fictional detectives of 1953-1964

James Bond wasn't alone - plenty of other hard men were packing guns between Dwight Eisenhower's first year in office and the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. Although less enthusiastically praised or studied then their heyday between 1930 and the end of World War II, the fictional detectives of the 1950s and 1960s, both public peace officers and private eyes, were still widely consumed on both sides of the Atlantic. Some were holdouts from an earlier, more refined era (Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple), while others indicated a savage new sensibility (Mike Hammer) that fit in well with a world gone nuclear. A few played roles in the eventual creation of James Bond, and until at least the release of first Bond film in 1962, most were more popular than Ian Fleming's international spy. Here are just a few of them.

American Ascendancy: After World War II, the world entered into a new, more potentially cataclysmic conflict. The Cold War, with its atomic bombs, spies, and traitors, helped to produce social paranoia of the type not seen since the First Red Scare after World War I. Red Scare number two proved longer and more angst-ridden than its predecessor, and in its wake came film noir. Coined by French film critic Nino Frank in 1946, film noir has come to mean a lot of things to a lot of different people. Some see it as an Americanised extension of German Expressionism, while others label it a trauma-driven art form full of existential dread and soul-searing loneliness. While film noir was both of these things and plenty more, it also offered a unique platform for tales of jaded cops, rugged PIs, and dames who could kill with their looks alone.

Building off the hardboiled framework that was established by Carroll John Daly and Dashiell Hammett during the 1920s, American detective fiction writers between 1953 and 1964 upped the ante in terms of sex and violence, and none more so than Mickey Spillane. In beer commercials and interviews, the Brooklyn-born Spillane talked like every bit the stereotypical working class, Irish American tough guy. He wrote exactly like that too, and in his Mike Hammer and Tiger Mann (a short-lived American version of James Bond who appeared in four novels between 1964 and 1966) novels, gritty realism, explicit sex, and near-pornographic levels of violence often overwhelm the sometimes simplistic plots involving revenge, gangland killings, and, frequently, communist plots to weaken the American status quo. Where the older detective novels of Agatha Christie and John Dickson Carr privileged complex crimes, investigative puzzles, and fancy manners, Spillane's tales amplified the sordid and tawdry and he became incredibly famous for doing so.

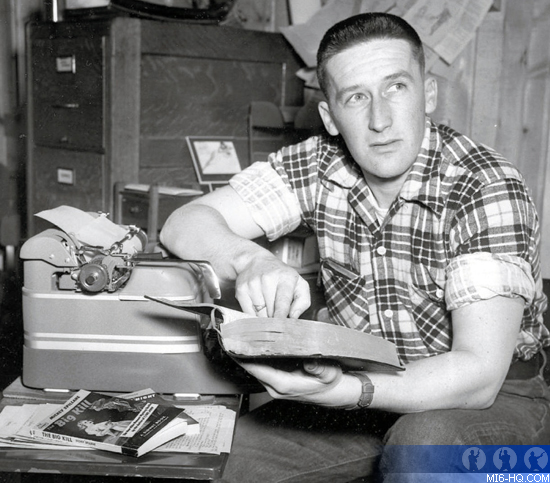

Above: Author Mickey Spillane poses with a copy of his 1951 novel, 'The Big Kill'

Although Spillane's detective novels sold well and his brand of .45 caliber justice appealed to a former intelligence officer named Ian Fleming, who would later cop to giving some of Hammer's sensibilities to his "blunt instrument" of the British government, Spillane was widely reviled by critics and peers alike. Often labeled a fascist, Spillane was accused of abusing and even distorting the rougher elements of the hardboiled school by Ross Macdonald, a fellow crime writer and the man behind Lew Archer, the postwar generation's answer to Raymond Chandler's Philip Marlowe.

Even though Chandler continued to write well into the 1950s ("The Long Goodbye", often regarded as his best work, was published in 1953), the imaginary torch had already been passed down to Macdonald, a California-born Canadian with a PhD from the University of Michigan, and thus Macdonald's Lew Archer novels became, for a while, the preeminent American detective stories. Called "the finest series of detective novels ever written by an American" by screenwriter William Goldman, Macdonald's Lew Archer novels again and again dealt with themes of familial guilt and paternal abandonment.

Above: Fleming's friend and fellow novelist, Raymond Chandler.

In many ways, Lew Archer and Mike Hammer form the ying and yang, the alpha and omega of American detective fiction during the era of Fleming's Bond novels and first films. Where Hammer was the gruff New Yorker who shot first and asked questions later, Archer was the more empathetic and intellectual Californian who was just as much a sociologist as he was a detective. When Macdonald finally managed to break out of the Chandlerian mould with 1958's "The Doomsters" the sharp differences between him and Spillane became even more pronounced.

The extent to which Macdonald influenced Fleming is unknown. While Fleming acknowledged his appreciation for Spillane's novels (this admiration was shared by Ayn Rand, who in turn lumped Spillane and Fleming together as two of the best thriller writers of the postwar years), his thoughts on Macdonald were never made public. That being said, Fleming was a big fan of Macdonald's hero Chandler, saying in a 1958 BBC radio interview that Chandler, his interview subject, wrote "some of the finest dialogue written in any prose today."

Other American detective fiction authors that Fleming also enjoyed were the prolific Rex Stout, the author of the very Nero Wolfe mysteries which M calls "readable" in "On Her Majesty's Secret Service", and the Harvard-educated John D. MacDonald. In an interview with Time magazine, Fleming admitted that "I automatically buy every John D. MacDonald as soon as it comes out." Although Fleming didn't live long enough to see the creation of MacDonald's most popular character, the Floridian "salvage consultant" Travis McGee, he did however live to see the publication of "The Executioners", the novel that would inspire the film Cape Fear.

Above: Ian Fleming at his Jamaican retreat, Goldeneye.

Brits Battle On: American crime fiction existed before the advent of the hardboiled school, but it was a pale imitation of the highly popular British style. From the creation of Sherlock Holmes in 1887 until the late 1940s, detective fiction was ruled by Britannia. The so-called Golden Age of Detective Fiction, which ran from approximately 1920 until 1939, helped to create popular legends out of such names as Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Margery Allingham. These novels, which became such unconscious self-parodies that they unintentionally helped to create a literary backlash that would later be dubbed "hardboiled," typically featured eccentric amateur sleuths, fashionable country manors or suburban homes, and ingenious murders which on the surface appeared impossible.

During the Golden Age and beyond, these novels have remained extremely popular, even despite the ubiquitous bad press they have received for so many years. That being said, the cozy mystery written in the standards of the Golden Age were almost phased out once the film noir era began in earnest. Some have seen this as part of a larger process of global Americanisation, as the cultural empire of the United States, which came with rock and roll, Hollywood blockbusters, and muscle cars rather than rifles, began to take root in the bombed and depleted countries of Europe.

Still, despite the proliferation of hardboiled private dicks, Britain managed to turn out talents such as P.D. James, H.R.F. Keating, and Josephine Tey, all of whom produced well-crafted and thoroughly British mysteries that proved internationally successful during the '50s and '60s. Fleming too can be considered a member of this group, for although James Bond is not a detective and Fleming did not specifically write detective fiction, the Bond novels not only borrowed much from their detective fiction forebears, but they also at times blurred the lines between the two genres, which have always been linked away. After all, after returning from his "death" at Reichenbach Falls, Holmes began taking on more and more government work until finally ending up a spy in "His Last Bow." Bond is nothing if not the logical extension of Holmes for the Cold War.

Above: A 19th century illustration by Sidney Paget of Bond's detective forbearer, Sherlock Holmes and companion Dr. Watson.

The Solid Man on the Continent: Before the frenzy over Scandinavian police procedurals, most English-speaking audiences gravitated to French detective novels if they wanted their crime in the Continental style. No French (well, actually Belgian) writer delivered the goods more than Georges Simenon, the workhouse wordsmith who created the everyman Inspector Maigret in 1931. Simenon's prodigious output and his longevity rivalled only Agatha Christie, and both saw their detectives working well into the 1970s. But while Christie dealt with the most unlikely of people, Simenon's crooks and manhunters remain believable portraits of French life. Fleming admired Simenon greatly, and both former journalists shared a fondness for drink, women, and the bon vivant lifestyle. Initially attracted by the jacket artwork on Simenon's books, Fleming once admitted to Simenon that he always read his books in the original French. Fleming especially liked reading Simenon whilst traveling in Europe.

On his end, Simenon had yet to read a single Bond novel before eventually meeting Fleming for a Harper's Bazaar interview in 1964. By the time the article was published, Fleming had already passed, but his eternal popularity was already well in place. Simenon, who was five years older than Fleming, would live for another twenty-five years. For eight of those twenty-five years, Simenon would continue to write Maigret novels at a steady clip, and despite his best efforts to remove big L literature from the equation, Simenon is now widely considered one of the 20th century's greatest writers. Maybe the same will hold true for Fleming some day. He's got the right literary friends, after all.